Introduction - can your theology handle the book of Lamentations?

Erik Raymond had a short article on Lamentations that was titled, "Can Your Theology Handle the Book of Lamentations?"1 I wished the article was longer, but I thought even the questions were helpful. He introduced the questions by pointing out that people tend to apologize to others for what the Bible says and tend to explain away difficult passages. Well, Lamentations is one of those difficult passages. So he asks - 1) Do you have a theology where God can get really angry and show it? Lamentations does. 2) Do you have a theology where man is really, really bad? Lamentations does; and it does so in such graphic language that it makes people cringe. They really don't think of themselves as being as bad as Lamentations says they really are. 3) Do you have a theology that can deal with the fact that even the righteous can experience pain, weeping, and anguish of heart like Jeremiah did? Lamentations has that kind of theology. 4) Do you have a theology where God's grace is really powerful and lavish - indeed, greater than the greatest of sin? Lamentations does. The description of God's grace in the heart of chapter 3 is astonishing, given the depth of sin and rebellion that this book has described. It is lavish grace.

The author for Lamentations & the setting

Now, all of those things can be found elsewhere too. But what is unique to Lamentations is that it teaches us what godly sorrow looks like through the tears of Jeremiah. Though there are many people who have questions over the authorship of this book, I believe the evidence is absolutely overwhelming that Jeremiah wrote it.2

He appears to have written it as Jerusalem lay in rubbles after Nebuchadnezzar leveled the temple and tore down the city walls. Before Jeremiah begins his own heart-rending river of tears in chapter 3, he sets the stage by portraying Jerusalem as a desolate widow in chapter 1. And even the rhythm of the Hebrew adds to the sadness of the poem.3 And there is no way of showing that to non-Hebrew readers other than having you listen to it. I happen to believe in the theory that the Masoretic diacritical marks show us the details of what the original music sounded like. There are some Psalms that are super upbeat. Others that are martial in feel. But I want you to listen to the first 33 seconds of the original inspired music of Lamenations 1.4 And this will be singing just verse 1.

[play]

Emotions expressed but under control

Does that sound like a person who is depressed and discouraged? It is. As Jeremiah sits in the smoking rubble of Jerusalem he likens it to a widow who has lost her husband, her home, and everything that belonged to her. This widow is devastated and Jeremiah is devastated with her. We will see in a bit that Jeremiah is devastated for different reasons than Jerusalem was, and that he teaches Jerusalem how to put off despair and how to put on a godly mourning. But Jeremiah himself is led by the Holy Spirit to weep with those who weep and to model what godly sorrow looks like. Relational wisdom 360 has lessons on how to grow in empathy - and Jeremiah had empathy in spades. He felt the hurt of others and wanted to minister to the hurt of others. And we will see that at least in Lamentations he stands as a type of Christ in that.

Why was Jeremiah even there? He had a choice. He could have gone to Babylon under the protection of the emperor and lived the good life, but he chose to stay. And I believe it was by the Holy Spirit's guidance that he did so. Jeremiah chose to identify with the smoldering hurt of his people. And as he sat in the dust and looked at this empty and desolate city, the tears start to run down his face as he says these words that were just sung in Hebrew,

Lam. 1:1 How lonely sits the city That was full of people! How like a widow is she, Who was great among the nations! The princess among the provinces Has become a slave! 2 She weeps bitterly in the night, Her tears are on her cheeks; Among all her lovers She has none to comfort her. All her friends have dealt treacherously with her; They have become her enemies.

And as the music goes on throughout the book, things get much more intense and emotional. The poetry and the music together are an amazing display of Jeremiah's emotions. But what many commentators have pointed out is that this is emotion under control. Jeremiah does not get hysterical. He does not start saying things that he would later regret. He models to us the godly emotion of sorrow and agony under the control of God's Spirit and under the self-discipline of his own spirit. And in doing so, models the difference between godly and ungodly sorrow. Too many people sorrow in a way that sins against God and sins against others. Jeremiah does not do that.

What do I mean by sorrow and emotion under control? The raw emotion is obvious; it is clearly on the surface. But where is the control? The control can be seen in the fact that every word and chapter is carefully structured so as to lead us to hope in God. It is a very disciplined writing out of his emotions. Let me explain:

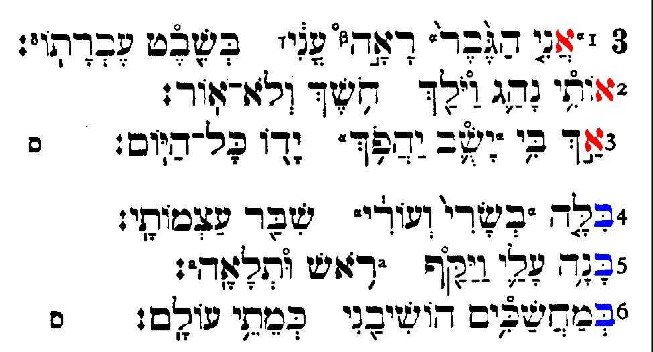

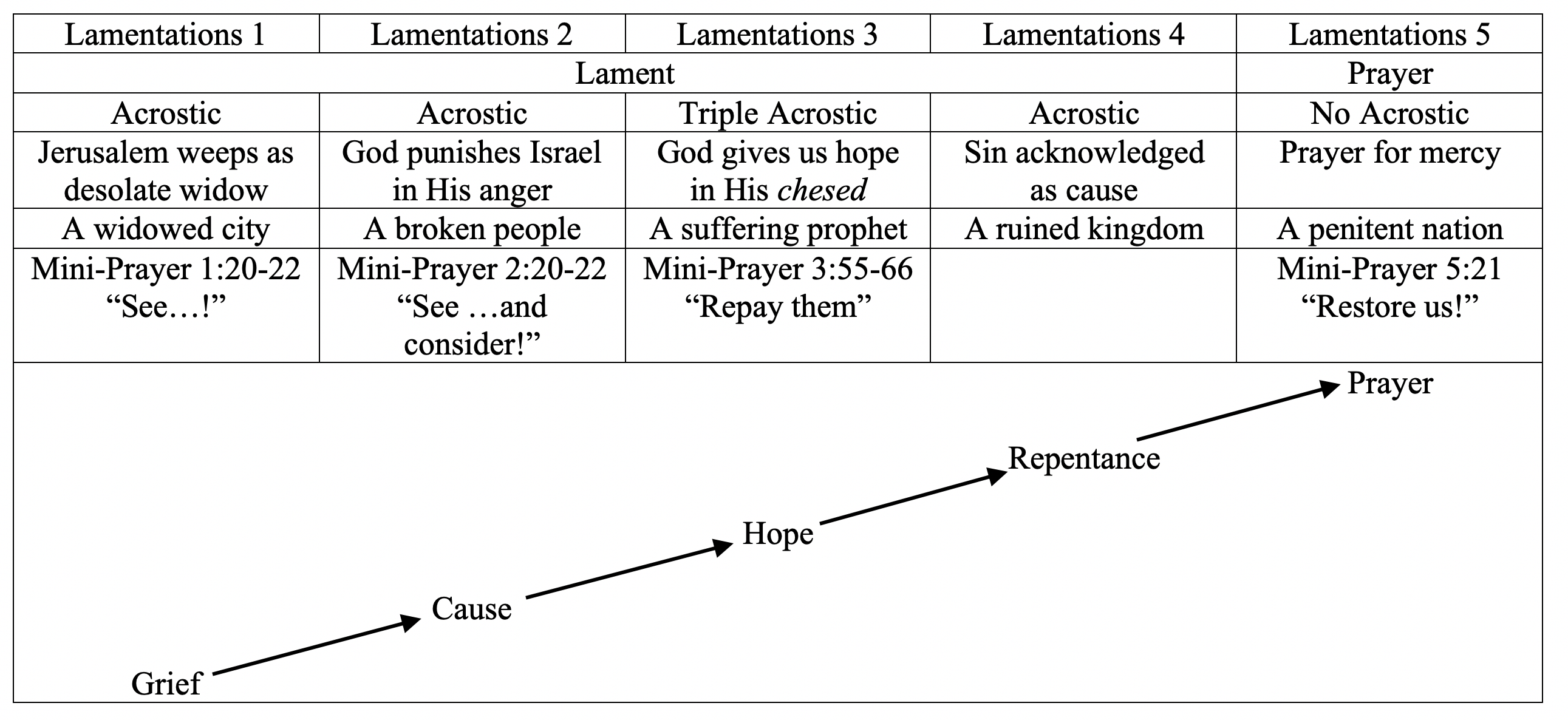

There are five poems, represented by the five chapters in our translation. Chapters 1,2,4, and 5 are words that Jeremiah gives to Jerusalem to say to lead the remnant away from despair and into a godly sorrow. Chapter 3 is Jeremiah's own words, or rather, Christ speaking those words through Jeremiah. And each of the poems has exactly 22 verses of poetry in the Hebrew, the number of verses in the alphabet. The first four of those chapters are acrostic in nature, with the first line of each verse beginning with the next letter in the Hebrew alphabet, from Aleph to Tau. And I have given a highlighted picture so that you can see that in the Hebrew. It is sort of like writing the A-Z of lamentations. So this is not a spontaneous lashing out. It is a very carefully and prayerfully thought through exercise in godly sorrow. He doesn't stuff his emotions. He unleashes his emotions in a healthy way that is totally under control.

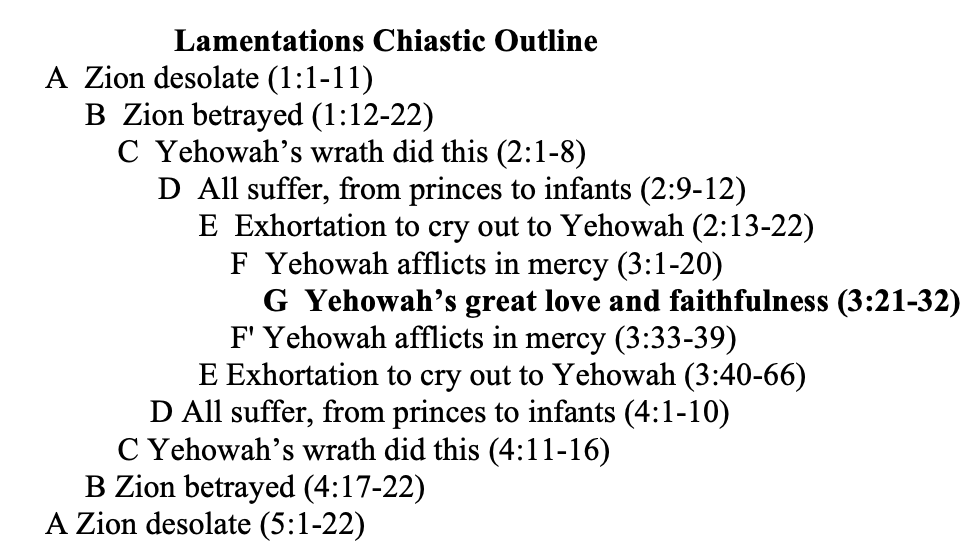

That control can also be seen in other characteristics of this book's form. Chapter 3, which forms the heart of the book, has a triple acrostic, where each line of each verse begins with the next letter of the alphabet. It's amazing. This makes the reader realize that something intense and special is going on with chapter 3. It sets that chapter apart from the others as being the very heart of the book. Of course the chiasm does that too.

And each couplet of every verse in the book follows the qinah rhythm of poetry. This is unique to Laments. You do not find it in any other kind of poetry. Where other poetry might have 3 accents on each couplet, qinah poetry has 3 accents and then 2 accents, giving it a weird dying feeling. But that is part of what gives it its emotion. So even though it expresses the raw emotion of grief, on many levels it is grief and sorrow expressed in a very controlled manner.

Chapter 3 is the heart of the book

Now, I mentioned that chapter 3 is the heart of the book. It represents Christ Himself experiencing this pain through Jeremiah. I'll try to prove that at the end, but let's just assume it for now.

The book as a whole is constructed as a chiasm. You might wonder why there are thirteen parts to the chiasm when there are only five poems. It is because there is a deliberate grammatical voice change that happens in a way that divides the book up into thirteen discrete units, and yet at those same time indicators deliberately tie all five poems together as one unit. And again, all of these things show that this is emotion under control. You can see the form of the chiasm in your outline:

If you look at the backside of your outline you will see a chart with progressive arrows pointing to five words at the bottom - with one word representing each chapter. They show how the structure of the book helps to resolve what starts off as the raw grief of a devastated widow in chapter 1, to understanding the cause of this devastation in chapter 2, receiving hope that the same God who afflicted her is the God of never ending mercies and faithfulness in chapter 3. This then gives a solid theological basis for calling her to repentance in chapter 4. And chapter 5 is the more refined prayer of the godly that contains repentance, expressions of pain, pleas for mercy, vindicating God as being rightly upset, asking God for relief, asking God to judge their enemies, and expressions of trust in God. It forms the conclusion, and it is set apart from the other chapters by having the same number of verses, but not being acrostic. It's the only chapter that is not acrostic.

Doug Wilson did a very short, but a very beautiful analysis of Lamentations showing how chapter 3 is the key to taking the sorrowing soul out of despair by giving hope and by sustaining the widow in the days of tears that are yet to come. Tears don't just shut off when we understand; but understanding can help to make the tears godly. Anyway, Wilson said,

What we gained at the center of the book, from our text, we are allowed to carry out with us. We walked through a desolate wilderness, found a great treasure, and are invited to carry that treasure out . . . through a desolate wilderness.5

So that's the big picture overview of the book. Let's go back through the book and seek to apply it to our lives.

Survey and application of the book

We've already seen that chapter 1 laments over the desolation of Jerusalem and likens the remnant who have survived to a devastated widow who has lost everything. There are two reactions that such a widow could have - she could lash out in bitterness against God and others or she could mourn in a way that leads her to God and to God's comfort. Both ways involve mourning, but only one leads to healing. Sadly, the first reaction is the natural impulse of our heart. Paul contrasted those two sorrows this way:

...you were made sorry in a godly manner, that you might suffer loss from us in nothing. For godly sorrow produces repentance leading to salvation, not to be regretted; but the sorrow of the world produces death. (2 Cor. 7:9-10)

And Lamentations is beautifully constructed to teach us how to sorrow in a way that leads to life rather than in a way that produces despair and even death. So chapter 1 is the desolated widow. Rather than letting the widow (Jerusalem) weep any way that she wants to weep, Jeremiah puts appropriate words into her mouth and calls her to have godly sorrow. What does that look like? Let me give you six things from his chapter that help to define it.

First, godly sorrow does not stuff our emotions or deny the pain. Chapters 1 and 2 definitely give us permission to cry and weep over the painful providences that God brings into our lives. That's OK. And denial is not helpful. There are many ways that people can be in denial and never properly engage in godly sorrow. Growing up as a bullied kid in boarding school I stuffed my emotions and took a Stoic grin-and-bear-it attitude, putting a fake smile on my face. I hardened my heart to pain, and in the process feared opening it up to love - because love meant vulnerability and pain all over again. So I stuffed my emotions. That's a form of denial. It is very unhealthy.

Another form of denial is a refusal to see God's hand in the pain, and instead only see others as the source and to lash out at those others. This was the problem with the revolutionaries who assassinated Gedaliah in Jeremiah 41 and kidnapped Jeremiah to Egypt. They saw the evil of Babylon and were lashing out at the only ones that they could see had brought pain into their lives, and in the process made life way worse for themselves. They left God out of the equation.

In Babylon there were false prophets who were predicting an immediate release. They were in denial about the seriousness of the situation. So there are many ways that we can be in denial. Those who are enablers of drunkards are engaging in a form of denial.

But in Lamentations, Jeremiah doesn't allow for that. The words of chapter 1 recognize the reality of her utter desolation in verses 1-7, the cause of her desolation in verses 8-11, encourage weeping over her sin and desolation in verses 12-19, and enable her to make confession to God in verses 20-22. That is godly sorrow. It weeps and agonizes over the loss, but it processes the reasons for that loss and allows those things to turn us to God.

Those who lash out at others rarely do the self-examination needed to see what God is doing in their own lives. They are so fixated on the evil of others that they are blinded to the good God is doing through that pain. They are so busy pointing the finger at the evil of Babylon (and Jeremiah doesn't deny that Babylon was evil; it was; but they are so busy pointing the finger at the evil of Babylon), that they fail to see any fingers pointing back at them. Jeremiah's lament makes it clear that none of these things was by accident. So the first thing you see here is that godly sorrow doesn't stuff emotions, deny that there is pain, or deny that we deserve it and worse - if God were to choose to give worse.

Second, Jeremiah gives counsel in each chapter to help the widow process what is happening. In verse 8 he says, "Jerusalem has sinned gravely, therefore she has become vile..." Unlike Job's afflictions, which were not the result of sin, these afflictions are the result of sin. Verse 9 says, "Her uncleanness is in her skirts; she did not consider her destiny; therefore her collapse was awesome; she had no comforters." So it is helpful to gain some understanding of why we are suffering. We can't always get that (as the book of Job showed so well), but if we can understand it, we can make adjustments.

Third, Jeremiah gives the widow permission to express the pain, frustration, and questions of "Why?" That is significant, since this pain was her own fault. But God still allows people to process the turmoil inside of them - of course, within guidelines. He does not let her lash out at God or others. But the words he puts into her mouth are filled with questions of Why? How long? Don't you care? Why am I left desolate? Will you abandon me forever?

I’ll just give you one example. In verse 12 she is allowed to in effect wonder, "Don't you care?" The Babylonians of course didn't care, but she can still ask inside of her head, "Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by? Behold and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow, which has been brought on me, which the LORD has inflicted in the day of His fierce anger." I find it significant that God Himself allows this widow to pour out her doubts, feelings of betrayal, and grief, even though it was her own fault. He corrects her, but he still sympathizes with her pain. It's an amazing balance. And it makes our God approachable to those who are hurting.

And by bringing up the fact that God inflicted this pain in His fierce anger shows a fourth thing that is important in godly weeping. We must acknowledge that God is sovereign over even the painful events that we experience. This may seem like a contradiction to the previous point, but it is not. And I will put a plug in for a book by Kay Arthur that discusses this far better than I can. It's her book, Lord, Heal My Hurts.6 God's sovereignty over our pain plays a big part in how she has successfully helped multitudes of women get past enormous pain in their lives. Now, God's sovereignty will be especially emphasized in chapter 2, but it is already starting to come up in chapter 1.

Fifth, one by one she lists the things that she is most hurt over. Jeremiah doesn't allow this to be a generalized undefined hurt, where you are just mad at a person but you don’t know why. She lists every hurt. In the process she can realize whether they are legitimate or not. She lists the obvious things of death, destruction, loss, hunger, mockery, and betrayal. Keep in mind that God is the one who is putting these words into her mouth. She isn't at chapter 5 yet. But to even get there, she needs to start listing out the hurts she has experienced. And most of these hurts were of her own doing. For example, verse 19 speaks of the enormous pain of betrayal. But who betrayed her? The lovers that she sinfully fornicated with. "I called for my lovers, but they deceived me." The fact that she shouldn't have had lovers did not mean that she shouldn't process the shock and pain that she is feeling from them. All of this will help her to turn away from such things and see the Lord as her only possession. I love the fact that God helps us with even the pains that are the result of our sins.

And after listing all of her pains, chapter 1 ends with a mini-prayer that Jeremiah puts into Jerusalem's mouth. It confesses sin, expresses sorrow over that sin, expresses weeping over the consequences of that sin, pleads with God to take away the pain and the loneliness and to punish the Babylonians, but then quickly remembers that this all came for her own sins. So it is a prayer that weeps yes, but it vindicates God, and resolves the sorrow in prayer to God. What we have seen in chapter 1 is the overall process of the book.

Chapter 2 focuses upon the ultimate determiner of all this mess. God was angry over the sins of Jerusalem and has punished her. That's it in a nutshell. Chapter 2 makes it crystal clear that none of these things happened by chance. God was the ultimate determiner of the Babylonian rape, pillage, murder, and destruction. And people cringe when they hear that. Their theology can't accommodate that. They try to defend God's reputation by explaining away the clear meaning of the text. But chapter 2 makes it clear that it was God who used Babylon, Edom, and other countries to put pain into Judah's life. Jeremiah minces no words about this. Chapter 2 says, "the LORD has covered the daughter of Zion with a cloud in His anger!" (v. 1). "He cast down from heaven to the earth the beauty of Israel." The Lord swallowed up and has not pitied. He has brought down strongholds to the earth. He has cut off in fierce anger every horn of Israel. He has drawn back His right hand. He has slain. He has poured out His fury. He has destroyed.

How could that be? Some of the things that the Babylonian's did were horribly sinful. They killed babies; they raped women; they pillaged; they took people captive. How could God be involved in that? James says that God neither sins, nor does He tempt others to sin. So how can He have providential control over even the sins of others? Romans 1-2 gives us a hint. It says that God gives us up to a depraved mind when we keep despising His grace and repressing the truth in unrighteousness. Let me use an illustration. The thing that holds this pen in the air is the restraining power of my hand. If I didn't hold it up, it would automatically fall to the ground of its own gravitational pull. In the same way, the gravitational pull of our sin natures makes every man, woman, and child tend to fall into every conceivable sin. God's restraining power keeps men from sinning as badly as they could sin just like I am holding up this pen and keeping it from falling. But when they persist in their rebellion, God gives them up. They don't deserve His continued restraint. In America we are seeing God giving up our own nation to incredible depravity. That would be like me removing my hand from this pen. The moment I do that, I have determined that the pen will fall. I don't force it to fall. I don't have to throw it down. It falls of its own accord. In the same way, when men persist in sin and God says, "You don't want me in your life? OK. I will give you up and see how you like the free fall." - when He does that, He ordains that they fall, but He didn't force them to fall, cause them to fall, or tempt them to fall. They fell of their own natures. God is sovereign over all things in life, but men are still responsible for their sins.

But lets suppose you don't believe that. The alternative is not pretty. If God's hand is not in it, then it is not working together for the good of the elect, his kingdom, or God's glory. If God's hand was not in it, then the only things that these people can process with are chance, evil men, and Satan. That is a recipe for despair. So the sovereignty of God is brought home to this widow over and over again in chapter 2. She must learn to process her grief with God.

I'm not saying that it is easy to acknowledge that God is sovereign over the dreadful and unjust things that happen to us. This whole book shows that it is not easy. It leads to tears. We just need to make sure that our tears are godly tears, not sinful tears. It's OK to pray imprecations against the Babylonians and Edomites who slaughtered babies. And Lamentations does so. God gives permission to do so. In fact, jumping ahead to chapter 3, in the prayer of Jesus through Jeremiah in chapter 3, the last three verses are a strong imprecation.

64 Repay them, O LORD, According to the work of their hands. 65 Give them a veiled heart; Your curse be upon them! 66 In Your anger, Pursue and destroy them From under the heavens of the LORD.

That prayer indicates that God does not at all justify the evil of the Babylonians. So just because we have to submit to God's providence does not mean that we have to agree with the evil. He will later judge the Babylonians and Edomites for the evil that they did.

But Jeremiah's perspective is that if God is not sovereign, why pray to Him or even complain to Him? If God is not sovereign, there is no logical way out of the cesspool of bitterness. But if God is sovereign, and if we see that His whippings are out of love (chapter 3), we can run into His arms and complain about the enemies out there and know that He does care and will take care of them. The imprecations of this book free us up from bitterness because we give the responsibility of judgment in God's hands. That frees us up to love our enemies - something that chapter 3 calls for. If God is sovereign, He can reverse our sad state when we repent, as God promises to do in chapter 3. If God is sovereign, we can pray against our enemies and leave the results in God's hands rather than getting bitter.

This doesn't mean that Jeremiah stuffs his emotions or calls the desolate widow to stuff her emotions. Godly sorrow may ask God, "Why?" or "How long?" but it may not deny God the right to afflict us. Godly sorrow may plead for mercy, but it may not complain that we deserve better - we don't. Godly sorrow may weep under afflictions, but it may not rail against God or cast Him off.

So you can see in your outline that the A sections of the chiasm give a vivid description of Zion's desolation, but the second A section (chapter 5) resolves that by praying to God in faith. Both B sections show that Zion was betrayed. But both B sections give partial resolution to this pain by looking to the Lord (1:20-22; 4:22). The C sections of the outline basically say that Yehowah's wrath has done all of this. But if God has brought the pain, then God is the solution to the pain, isn't He? And actually, another book that I would like to recommend is John Piper's book, Don't Waste Your Cancer.7 It's an amazing treatment of how our pains can cause us to grow if we are willing.

The D sections are particularly tough because they not only show desolation upon leaders who deserved it, but upon infants and young children who suffer along with everyone else. They speak of children starving and dying and mothers eating their own children. And yet Jeremiah's inspired words attribute even those troubles to the Lord.

The E sections of the chiasm give Jeremiah's exhortation to cry out to Yehowah. Why? Because the F sections show that Yehowah afflicts in mercy. The first F section speaks of the rod of God's correction (the shebet שֵׁבֶט - is a loving rod of correction) and the second F section encourages people to submit to God's chastening and learn from it. Don't be dancing around when God spanks. Submit to His spanking.

But it is the central section of this book that gives such beautiful instruction for the right attitude to undergird our sorrows. And I want to finish this sermon by going through chapter 3:21-32 verse by verse. This is the heart of the book.

After reminding himself that Yehowah chastises us in mercy, verse 21 says,

21 This I recall to my mind, Therefore I have hope.

Understanding God’s nature can turn abject despair into weeping with hope. Hope is compatible with godly sorrow and weeping, but ungodly sorrow robs the heart of hope. So you can test the nature of your sorrow by seeing if you refuse any hope at all. If you have no hope, you are not approaching your sorrows in faith. Verse 22:

22 Through the LORD’S mercies we are not consumed, Because His compassions fail not. 23 They are new every morning; Great is Your faithfulness.

Those two verses are a condensation of incredible theology. It is of the Lord's very nature to have mercy. The Hebrew term for that, chesed, goes way beyond mercy. It is variously translated as loyalty, faithfulness, covenant love, steadfast love, mercy, lovingkindness. It is a word that woos the heart to God rather than making us run from Him. When we sorrow, we must remind ourselves that our God is a God of chesed. His rod of discipline is because of His loyalty to us; His love to us; His faithfulness to us; His mercy to us. Even in the pain He wants the best for us. And we should run into His arms after a whipping.

And it was precisely because of His chesed that the entire nation was not wiped out. God preserved a remnant in Babylon. Not all were consumed in His wrath. But Jeremiah's prayer assumes that God would have been perfectly just to have killed more of them. None of them deserved life. It is "through the LORD’S mercies we are not consumed."

He then states, "because His compassions fail not." That word refers to tender mercies or sympathetic love that a mother might have for a helpless baby. It is another dimension of God's love that keeps us from despair. It is because of a mom's compassions that a child who has been disciplined by her still runs into her arms. Our theology of God makes a huge difference on how we sorrow.

When Jeremiah says that God's mercies are new every morning, it implies that we sin daily and nightly. That thought will give us humility in our sorrow. It's not that God's mercies were absent from the widow. It's just that she was not seeing them. Jeremiah helps give perspective that it is a mercy that they are still alive.

And then comes my favorite phrase in the whole book, "Great is Your faithfulness." This is the phrase that made Thomas Chalmers write his magnificent hymn, "Great is Thy Faithfulness." We will sing this immediately after the sermon. James Smith says,

This great affirmation of faith came from the lips of a man who had recently suffered what few others before or since have suffered. It was a time when men had only the most meager provisions. Every morsel of bread, every cup of water, every tattered garment was regarded as an evidence of the mercies of God.8

He goes on to say in verse 24:

24 “The LORD is my portion,” says my soul, “Therefore I hope in Him!”

This is such a contrast to the group of revolutionaries who put their trust in power. It's such a contrast to the false prophets who put their trust in a fantasy. When people despair, they are like a drowning man who grasps at straws that will not hold him up. It doesn't mean that we always understand what God is doing. But believers know that if they had to lose everything or lose God, they choose God as their portion. I think of the disciples in John 6. Jesus had offended the crowds so that virtually everyone abandoned Him. Jesus asked his twelve if they wanted to leave too. Peter didn't deny that he was uncomfortable, but his answer is revealing. He said, "Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life" (John. 6:68). We may not understand what You are doing, but we are sticking by You. The Lord is my portion, therefore I hope in Him. Verse 25:

25 The LORD is good to those who wait for Him, To the soul who seeks Him.

Never did Jeremiah question God's goodness. In our pain we might be tempted to, but we must not. Jeremiah might have wondered why he had to suffer all of his pain, but he never questioned God's goodness.

And by the way, "waiting on the Lord" is never a passive inactivity. We don't just crawl in a hole and wait for the world to go away. That's a sure recipe for disaster. Depressed people want to crawl into a hole, but they should not. The second half of the couplet defines waiting for God as seeking God. Those who seek God have this as one of their most ultimate presuppositions. God is good. That's why they seek Him.

Verses 26-32 show more characteristics we should have when the Lord brings disciplines.

26 It is good that one should hope and wait quietly For the salvation of the LORD.

He calls for hope for the future. He calls for an active waiting upon the Lord - that means praying. And he calls for a quiet attitude. He is not contradicting the fact that this book has encouraged words of sorrow. This is not referring to a physical silence, but a quiet attitude under discipline that does not lash out, act sullenly, or even run. It quietly takes the discipline and treats the discipliner as one who loves us and has our best interests in mind. Verse 27:

27 It is good for a man to bear The yoke in his youth.

If you learn to bear suffering well in your youth, you will not so easily despair when you are old. Verse 28:

28 Let him sit alone and keep silent, Because God has laid it on him;

These people were captives, and Jeremiah is telling them to control their emotions in front of their captors. This would make the captives seem remarkable to the Babylonians. There is something different about them. So Ecclesiastes 3 says there is a time to turn off tears; a time when it is inappropriate to cry. The cries of this book are a crying out of our hearts to God, but also show the ability to control our tongues before men. Again, it shows control of the emotions. Verse 29 says,

29 Let him put his mouth in the dust— There may yet be hope.

Putting your mouth in the dust is an attitude of humility. I bow before You Lord and receive this discipline in humility. When you have a humble attitude in the face of His disciplines, God loves to bless. Verse 30:

30 Let him give his cheek to the one who strikes him, And be full of reproach.

Abner Chou comments, "Putting these ideas together, the writer encourages his readers to endure the full bout of humiliation in exile."9 They would bear a great deal of humiliation and reproach in the first years of their exile, but submitting without bitterness would get them further than striking back. And by the way, this is probably the passage that Jesus referred to when He called us to turn the other cheek. And since God is in it, there is no reason to be bitter. In fact, the reason we can have such an attitude towards our pain is given in verses 31-32:

31 For the Lord will not cast off forever. 32 Though He causes grief, Yet He will show compassion According to the multitude of His mercies.

This is not just a promise of return from exile. I think it is primarily saying that when we have learned our lessons, God loves to exalt us. He exalts the humble. And if you study the history of the exiles you find that the exiles were hugely exalted by God in the empire of Babylon, entering into some of the best positions, jobs, and places of influence. God's compassion and the multitude of His chesed guarantees a beneficial outcome.

Verse 33 goes on to say, "For He does not afflict willingly, nor grieve the children of men." It's not like God gets joy from bringing pain any more than you would find joy in taking your child through the painful procedures to recover from cancer. But it is still love that does so. So all of those points form the background to godly weeping and sorrow.

Does the realization of all of these truths stop the weeping right away? No. Even after all of the glorious theology of chapter 3, verses 48-50 still have Jeremiah saying,

My eyes overflow with rivers of water for the destruction of the daughter of my people. My eyes flow and do not cease, without interruption, till the LORD from heaven looks down and sees.

He has to keep reminding Himself of the Lord's care as he continues to experience the wilderness. When we are going through great emotion we have to keep reminding ourselves, preaching to ourselves, and giving ourselves perspective. Godly sorrow does not automatically happen. We need to fight for it. But the main point is that this theology of God's goodness, faithfulness, compassion, even God's own pain as He disciplines us, does not necessarily take away our pain, tears, or grief. But it sustains us in that pain and helps us to move to God rather than away from God.

Jeremiah would continue to face some wilderness as the revolutionaries in Jerusalem kidnapped him, took him to Egypt, and when he didn't cooperate with him, stoned him to death. It wasn't a pleasant end, and yet he could say in the midst of his tears just like Job did, "Though He slay me, yet will I trust Him." "The Lord is my portion... Therefore I hope in Him." So this is a book that teaches us how to avoid the extremes of denial on the one hand or despair on the other hand. It calls us to weep with hope. As Doug Wilson said,

What we gained at the center of the book, from our text, we are allowed to carry out with us. We walked through a desolate wilderness, found a great treasure, and are invited to carry that treasure out . . . through a desolate wilderness.

The Christ of Lamentations - chapter 3

Let me make one last comment, and that is on the Christ of Lamentations. Certainly there is the altar and temple that is said to be abandoned by God. And this book stands as a prophetic statement about the temporariness of the temple. Chapter 4's statement, "How the gold has become dim" is a beautiful metaphor of how dim the redemption pictured in the temple was compared to Jesus. So we do see Christ in those statements.

But it is in chapter 3 in particular that we see the voice of Christ speaking through Jeremiah. Last week I gave ten comparisons between Jeremiah and Jesus in the book of Jeremiah. I said that while I find those comparisons intriguing, I don't necessarily find them sufficient to make Jeremiah a type of Christ - at least in the book of Jeremiah. But Richard Pratt convinced me this week that when you combine those images of Jeremiah together with chapter 3 of this book, that Jeremiah does indeed stand out as a type of Jesus entering into our pains.

Chapter 3 begins, "I am the man who has seen affliction by the rod of His wrath." Not, "I am a man," but "I am the man." When this is combined with the fact that many of phrases in this chapter are elsewhere said to be the very words of Jesus, I believe that this is God the Son speaking through Jeremiah and entering into our pain.

Of course, not everyone believes that. Some say that this is Zion collectively speaking. That makes sense of certain features of the chapter. But verse 1 explicitly calls Him "the man" rather than "the woman," as she appeared earlier. And verse 14 has this man speaking of "my people." The corporate view cannot adequately account for the man being different than the people. But if it is Christ speaking through Jeremiah, then since Christ is the head of the body, He can speak on behalf of the body, but since He is also distinct from the body, He can speak of my people.

Another view is that some individual, whether Jeremiah or some other individual, is speaking about his own suffering. But other commentators point out that while this does account for certain verses, it cannot account for the "we" passages where this speaker represents the suffering remnant. It also fails to show how this chapter is tightly connected with the other chapters. But if it is Christ speaking through Jeremiah, then He speaks in much the same way that Christ did to Saul in Acts 9, saying, "Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting Me." Christ so entered into union with His elect, that when they were persecuted He was persecuted; when they suffered He suffered. And thus Paul could speak of filling up what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ. He said, "I now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up in my flesh what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ, for the sake of His body, which is the church..." (Col. 1:24). He's not saying that Christ needed more sufferings to atone. No, that work was finished. The only way that verse makes sense is that Christ ordained for Himself to continue to experience ongoing sufferings with His church and until the last sufferings of saints is finished on earth, Christ is ordained to continue to experience our afflictions. Every affliction you go through is filling up the afflictions of Christ.

Now, certainly Jeremiah could be simply praying this as a type of Jesus, but since he is not mentioned, and since almost every verse in chapter 3 could showcase Jesus suffering on behalf of His people, it is possible that the whole of chapter 3 is Christ speaking out the sufferings of His body, the remnant. But at a minimum, Jeremiah stands as a type of Christ - the Christ who sympathizes with you; empathizes with you; enters into your sufferings with you. And for that we can praise Him. Amen.

Footnotes

-

Erik Raymond, "Can Your Theology Handle The Book of Lamentations," blog article April 20, 2016, on The Gospel Coalition. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/erik-raymond/can-your-theology-handle-the-book-of-lamentations/ ↩

-

Some of the evidence includes: 1) Jeremiah is said to compose laments in 2 Chron. 35:25, and is therefore at least familiar with the lamentation-type of literature. 2) The earliest written source is a Greek version of Lamentations that prefaces it with “And it came to pass after Israel was carried away captive and Jerusalem was made desolate that Jeremiah sat weeping, and he lamented with this lamentation over Jerusalem, and he said...” 3) The Latin Vulgate has the same ascription. 4) The Targum of Jonathan (AD 100 BC) ascribes the book to "Jeremiah the prophet." 5) The Talmud says, "Jeremiah wrote his book, Kings, and Lamentations." 6) All the ancient Church Fathers ascribed Lamentations to Jeremiah. And even the most radical critics who deny that Jeremiah was the author agree that there are many internal evidences that parallel the book of Jeremiah. They tend to focus on the differences, but this is after all a book of five poems. There are going to be differences between poetic literature and prophetic literature. But there are striking similarities between portions of Lamentations and certain sections of Jeremiah. For example, compare Lam. 1:2 with Jer. 30:14; Lam. 1:15 with Jer. 8:21; Lam. 1:16 and 2:11 with Jer. 9:1,18); Lam. 2:22 with Jer. 6:25; Lam. 4:21 with Jer. 49:12. The author clearly was an eyewitness of the siege and fall of Jerusalem (see 1:13-15; 2:6,9; 4:1-12). This fits Jeremiah who remained behind after the captives were deported in Jeremiah 39. ↩

-

Laments like this one differ from other forms of poetry in their structure. Instead of the standard couplet with 3 stresses in each line of the couplet, every verse of Lamentations has an unequal couplet with the first line having 3 stresses and the second line having 2 stresses. This gives a trailing off or dying effect that adds to the feeling of sorrow. ↩

-

One example of performances of the original tunes of Scripture can be purchased is here https://www.allmusic.com/album/the-music-of-the-bible-revealed-mw0001940743 For the book that set these studies off, see https://smile.amazon.com/Music-Bible-Revealed-Deciphering-Millenary/dp/094103710X/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=The+Music+of+the+Bible+Revealed%3A+The+Deciphering+of+a+Millenary+Notation&qid=1571514511&sr=8-1 ↩

-

https://dougwils.com/the-church/s8-expository/surveying-the-text-lamentations.html ↩

-

https://smile.amazon.com/Lord-Heal-Hurts-Devotional-Deliverance/dp/1578564409/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1EV22GZR4YMKW&keywords=lord+heal+my+hurts+by+kay+arthur&qid=1571343529&sprefix=Lord+heal+my+%2Caps%2C152&sr=8-1 ↩

-

https://smile.amazon.com/Dont-Waste-Your-Cancer-Piper/dp/1433523221/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=John+piper+don%27t+waste+your+cancer&qid=1571344219&sr=8-1 ↩

-

James E. Smith, An Exegetical Commentary on Lamentations (College Press, 1972), p. 21. ↩

-

Abner Chou, Lamentations: Evangelical Exegetical Commentary, Evangelical Exegetical Commentary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2014), La 3:30. ↩